David Brooksfs column today is a suggested opening for his Wednesday night debate. It includes this gbrutal truthh about Medicare costs: gNobody knows how to reduce health-care inflation.h

Itfs would be a pretty brutal truth except for the fact itfs not really true at all: We have a lot of examples to look at where governments have successfully held down the rate of health-care cost inflation. Most of them do that through some version of price controls, where the government sets the rates that doctors can charge for various services.

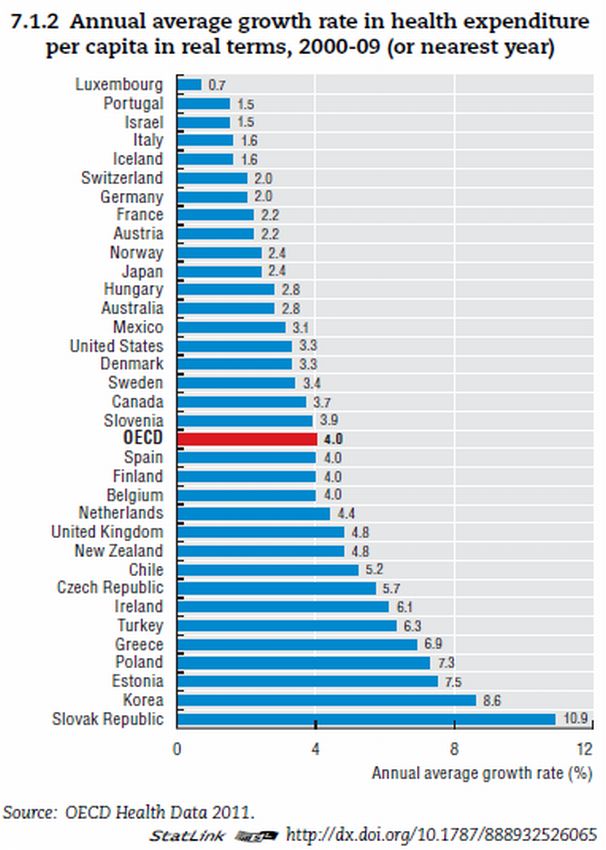

There are a handful of developed countries that have seen health-care inflation grow relatively slowly over the past decade, the ones at the top of this chart from the OECD:

Letfs focus on a few of the countries that have seen health-care costs grow slower than 2 percent, starting with Luxembourgfs very low 0.7 percent growth. Their system allows patients free choice of what doctor to see or hospital to visit but has the government set all rates for what doctors get paid for those visits.

Then therefs Israel, which has done way better on controlling costs than most other developed nations. They too have gotten there through a system in which the government sets the rates that doctors and hospitals get paid. Herefs what two researchers, publishing in the journal Health Affairs, wrote about the Israeli health-care system in a recent article:

The national government exerts direct operational control over a large proportion of total health care expenditures, through a range of mechanisms, including caps on hospital revenue and national contracts with salaried physicians. The Ministry of Finance has been able to persuade the national government to agree to relatively small increases in the health care budget because the system has performed well, with a very high level of public satisfaction.

It turns out that we donft even have to look internationally to find an example of success at holding down health cost inflation: Maryland has been quite successful at this for about four decades now. It is the only state that uses rate-setting for hospitals, meaning that the state government decides what all Maryland hospitals can charge for a given procedure.

That system went into effect in 1976, when Maryland had hospital costs 26 percent higher than the rest of the the country. Just over three decades later, in 2008, the average cost for a hospital admission in Maryland was down to national levels. hFrom 1997 through 2008, Maryland hospitals experienced the lowest cumulative growth in cost per adjusted admission of any state in the nation,h the state concluded in a 2010 report.

Rate-setting isnft very well-liked in the United States. About 30 states implemented schemes similar to Marylandfs in the 1990s but have repealed them since. The heavy-handed approach proved unpopular, and states shifted toward managed care as their cost-control method of choice.

Rate-setting has a pretty decent track record in holding down health-care inflation but less of a stellar scorecard in American politics. In a way, the success of rate-setting makes pretty simple sense: When the government has the final say on how much a medical procedure costs, itfs pretty easy to hold down the price.